The parent teacher conference represents one of the most valuable opportunities in education—a dedicated time when families and educators come together to discuss a child’s progress, challenges, and potential. These brief meetings, typically lasting just 15-20 minutes, can profoundly impact student success when approached thoughtfully by both parties.

Yet many parents feel uncertain about what to expect during these conferences or how to make the most of limited time. Teachers, meanwhile, often juggle dozens of conferences in compressed timeframes, making preparation and focus essential on both sides. When both parents and teachers come prepared with clear goals, relevant questions, and collaborative mindsets, conferences transform from routine check-ins into powerful partnerships supporting student growth.

This comprehensive guide walks you through everything you need to know about parent teacher conferences: what typically happens during these meetings, how to prepare effectively, which questions to ask, how to discuss concerns constructively, and how to follow up afterward. Whether you’re a first-time parent attending your child’s first conference or a veteran navigating new grade levels, these insights will help you approach conferences as collaborative opportunities rather than sources of anxiety.

Understanding the Purpose of Parent Teacher Conferences

Before diving into preparation strategies, it’s helpful to understand what these conferences aim to accomplish and why schools prioritize them despite logistical challenges.

The Core Objectives

Parent teacher conferences serve multiple essential functions in the educational ecosystem. At their foundation, conferences provide opportunities to share information about student progress beyond what report cards can convey. Teachers communicate observations about academic performance, work habits, social interactions, and classroom behavior, while parents share insights about home circumstances, outside interests, learning preferences, and any factors influencing school performance.

These meetings also create space for collaborative problem-solving when challenges arise. Whether addressing academic struggles, behavioral concerns, social difficulties, or motivation issues, conferences allow teachers and parents to coordinate strategies ensuring consistent support across home and school environments.

Perhaps most importantly, conferences help build relationships between families and educators. When teachers and parents know each other as partners invested in the same child’s success, ongoing communication becomes easier and more effective throughout the school year.

Traditional vs. Student-Led Conferences

Conference formats vary across schools and grade levels. Traditional conferences involve parents meeting with teachers while students wait elsewhere or stay home. This format allows candid adult conversations about concerns without students present, though it can feel like adults discussing children rather than with them.

Increasingly, schools implement student-led conferences where students present their work, explain their progress, and participate in goal-setting conversations alongside parents and teachers. This approach promotes student ownership of learning, develops self-advocacy skills, and ensures students hear consistent messages from both adults. However, it may limit adults’ ability to discuss sensitive concerns requiring privacy.

Some schools adopt hybrid models combining brief student-led presentations with private parent-teacher conversations. Understanding which format your school uses helps you prepare appropriately and set realistic expectations.

Timing and Frequency

Most schools schedule formal conferences twice yearly—typically in fall (October or November) after teachers have had time to know students and again in late winter or spring (February or March) to assess progress toward year-end goals. Some schools schedule additional conferences as needed for students experiencing significant challenges or making exceptional progress.

Conference timing influences what you should focus on. Fall conferences often emphasize getting to know your child’s teacher, understanding classroom expectations, establishing communication preferences, and addressing any early concerns before they become serious issues. Spring conferences typically focus on year-end goals, next grade preparation, summer learning recommendations, and celebrating growth achieved.

Preparing for Your Parent Teacher Conference

Thoughtful preparation ensures you make the most of limited conference time. These strategies help you arrive ready for productive conversations.

Gathering Information in Advance

Before your scheduled conference, collect relevant information that will inform your discussion. Review recent work samples including graded assignments, tests, projects, and homework your child has brought home. Look for patterns in strengths and struggles rather than fixating on individual grades. Notice whether errors suggest conceptual misunderstandings, careless mistakes, incomplete effort, or other underlying issues.

Check online gradebooks and learning management systems if your school uses them. Many schools provide parent portals showing current grades, missing assignments, attendance records, and teacher comments. Reviewing these beforehand prevents using conference time for information you could access independently.

Talk with your child about their school experience. Ask open-ended questions about what they enjoy, what they find challenging, how they feel about their teacher and classmates, and whether they need help with anything. Their perspective provides valuable context for your conference conversation. For older students, consider asking what they’d like you to discuss or avoid discussing with their teacher.

Document any concerns you want to address, whether academic struggles, behavioral issues, social challenges, or questions about teaching methods. Writing them down ensures you don’t forget important topics when caught up in conversation.

Preparing Questions to Ask

Arriving with prepared questions demonstrates your engagement while ensuring you gather information most valuable to you. Consider asking some of these questions, adjusting based on your child’s grade level and specific circumstances:

Academic Progress Questions:

- How is my child performing relative to grade-level expectations?

- What are my child’s greatest academic strengths?

- In which areas does my child need the most improvement?

- Is my child participating actively in class discussions and activities?

- How does my child approach challenging work or new concepts?

- Are there any learning gaps from previous grades affecting current performance?

Work Habits and Behavior Questions:

- Does my child complete and turn in assignments on time?

- How is my child’s focus and attention during lessons?

- Does my child ask for help when needed?

- How does my child respond to feedback and correction?

- Is my child organized with materials and responsibilities?

- How does my child handle frustration or setbacks?

Social and Emotional Questions:

- How does my child interact with classmates?

- Does my child have friends and positive peer relationships?

- How does my child handle conflicts or disagreements?

- Does my child demonstrate confidence or struggle with self-esteem?

- Are there any behavioral concerns in the classroom or on the playground?

Support and Intervention Questions:

- What can I do at home to support what you’re teaching?

- Are there specific skills we should practice?

- Should we consider any interventions, accommodations, or enrichment opportunities?

- How can we best communicate throughout the year?

- What signs of progress or concern should I watch for?

For students with individualized education plans or 504 accommodations, prepare specific questions about how supports are being implemented and whether modifications are proving effective.

Logistical Preparation

Handle practical details that help conferences run smoothly. Confirm the date, time, and location of your conference. Note whether it’s in the teacher’s classroom, library, or other location. If multiple children attend the same school, verify you haven’t been scheduled for overlapping conference times.

Arrive on time, recognizing that teachers typically schedule conferences in tight succession with little buffer time. Late arrivals cut into your own conference time and disrupt the teacher’s entire schedule. If you’re running late, contact the school to inform them rather than simply not showing up.

Arrange for childcare if possible. Conferences work best when parents can focus fully on the conversation without managing younger siblings. If you must bring other children, prepare quiet activities to keep them occupied and consider whether the teacher’s classroom setup accommodates additional children safely.

Bring a notebook and pen to take notes about important information, action items, or follow-up needed. Conferences involve substantial information that’s easy to forget later without written reminders.

What to Expect During the Conference

Understanding typical conference structure helps you feel more comfortable and use time effectively.

Standard Conference Flow

Most conferences follow similar patterns, though individual teachers may adapt based on their style and your child’s specific needs. The teacher typically begins with positive observations about your child’s strengths, contributions, or growth. This isn’t just politeness—every child has positive qualities worth celebrating, and beginning positively sets a collaborative rather than defensive tone.

The conversation then shifts to academic performance across subjects or skill areas. Teachers share information about current achievement levels, progress over time, work samples demonstrating understanding or areas needing improvement, and standardized test results if available. They may show you your child’s portfolio, explain the curriculum being taught, and contextualize how your child’s performance compares to grade-level expectations.

Next comes discussion of work habits, behavior, and social development. Teachers share observations about your child’s attention, organization, effort, classroom participation, peer interactions, and any behavioral patterns—both positive and concerning. This holistic perspective recognizes that academic success depends on more than just cognitive ability.

The teacher will likely ask about your observations and concerns from home. This is your opportunity to share information that helps the teacher understand your child more completely—learning preferences, outside interests and activities, family circumstances affecting school performance, concerns you’ve noticed, or questions you prepared.

Finally, conferences should conclude with goal-setting and action steps. What specific objectives will everyone work toward? What will the teacher do at school? What will parents do at home? When and how will you check in on progress? Clear next steps transform conferences from information exchanges into launching points for coordinated support.

Throughout, expect honesty balanced with respect. Good teachers share concerns directly while maintaining respect for your child and family. If a teacher raises a concern, they’re not attacking your child or your parenting—they’re flagging an issue so you can address it together before it worsens.

Time Management Realities

Conference slots typically run 15-20 minutes, occasionally 30 minutes for students with complex needs. This limited time requires focus from both parties. Teachers juggle dozens of conferences compressed into one or two days, creating both time pressure and mental exhaustion. Understanding these constraints helps you use time wisely.

If your concerns require more time than the standard slot allows, don’t try to force everything into one meeting. Instead, use the conference to establish priorities, gather initial information, and schedule a follow-up meeting or phone call to continue the conversation with adequate time. Teachers appreciate parents who recognize time limitations and work within them rather than monopolizing time needed for other families.

Discussing Concerns Constructively

When concerns arise—whether yours or the teacher’s—how you approach these conversations significantly impacts their productivity.

When Teachers Raise Concerns

If a teacher shares concerns about your child’s academic performance, behavior, or social development, your initial reaction may be defensiveness, denial, or worry. These emotions are natural, but managing them allows for more productive conversations.

Listen fully before responding. Let the teacher completely explain their observations, share specific examples, and describe patterns they’ve noticed. Avoid interrupting with justifications or contradictions until you’ve heard their complete perspective.

Ask clarifying questions to ensure you understand the concern accurately. Request specific examples: “Can you give me an example of when this happened?” or “What does this look like in the classroom?” General statements like “He’s struggling” become more actionable when you understand specific behaviors or skill gaps.

Acknowledge the concern without immediately accepting blame or making excuses. Responses like “Thank you for bringing this to my attention” or “I appreciate you noticing this pattern” recognize the teacher’s observations without committing to any particular interpretation or action until you’ve had time to process and respond thoughtfully.

Share your perspective including relevant context the teacher may not know. Perhaps your child struggles with anxiety that surfaces as defiance, or recent family stress is affecting concentration, or similar patterns have occurred in past grades. This information helps teachers understand root causes rather than just surface behaviors.

Collaborate on solutions by asking “What strategies do you recommend?” or “How can we work together on this?” Position yourself as a partner invested in improvement rather than an adversary defending your child or an uninvolved party delegating the problem entirely to the teacher.

When You Have Concerns

If you’re worried about your child’s experience—whether academic, social, or behavioral—the conference provides an opportunity to address concerns directly with someone who sees your child in a different context.

Present concerns as observations, not accusations. Frame your worry as “I’ve noticed…” or “I’m concerned that…” rather than “You aren’t…” or “The classroom isn’t…” This approach invites problem-solving rather than defensiveness.

For example, instead of “You’re not challenging my child enough,” try “I’ve noticed my child finishes work quickly and seems bored with assignments. Are there opportunities for more challenging work?” The first feels like an attack; the second invites collaborative problem-solving.

Provide specific examples of what you’ve observed at home. Vague concerns like “My child doesn’t like school” give teachers little to work with. Specific observations like “My child cries every morning before school and says nobody will play with him at recess” or “My child becomes extremely frustrated with math homework and shuts down” help teachers understand exactly what’s happening.

Seek the teacher’s perspective by asking whether they’ve noticed similar patterns at school. Sometimes issues surface primarily at home, sometimes primarily at school, and sometimes in both contexts. Understanding where and when problems occur reveals important information about causes and solutions.

Avoid comparing your child to siblings, classmates, or your own childhood experiences as this rarely helps. Focus on your actual child’s actual needs in their actual current situation rather than what worked for someone else in different circumstances.

Navigating Disagreements

Occasionally, parents and teachers genuinely disagree about a situation, appropriate interventions, or the severity of a concern. When this happens, focus on finding common ground while respecting different perspectives.

Identify shared goals even amid disagreement about methods. Both of you want your child to succeed academically, develop positive peer relationships, and feel safe and supported at school. Starting from this common ground creates foundation for working through disagreements about specific approaches.

Ask about the evidence or reasoning behind the teacher’s perspective. Understanding their logic may reveal valid points you hadn’t considered, even if you ultimately disagree with their conclusion. Similarly, explain your reasoning so they understand your perspective isn’t arbitrary.

Propose trial periods for disputed interventions. If you disagree about whether your child needs extra support, suggest trying the support for a defined period (say, 6 weeks) with clear criteria for assessing whether it’s helping. If you disagree about a behavioral consequence, propose an alternative approach for a trial period with agreed-upon outcomes to measure success.

Know when to escalate if conversations with the teacher don’t resolve significant concerns. Your child’s school has administrators, counselors, special education coordinators, and other resources that may help when teacher-parent collaboration alone isn’t sufficient. This isn’t “going over the teacher’s head” vindictively—it’s accessing additional expertise for complex situations.

Specific Conference Scenarios and How to Handle Them

Different situations require different approaches. These scenarios address common conference circumstances.

Conference for Students Struggling Academically

When your child falls behind academically, conferences should focus on understanding why and developing coordinated support strategies.

Distinguish between “can’t” and “won’t” problems. Does your child lack the foundational skills or understanding needed for current work (a “can’t” problem requiring instruction), or do they have the capability but aren’t applying effort (a “won’t” problem requiring motivation)? These require different interventions.

Ask about prerequisite skills from earlier grades that might be missing. Current struggles often stem from foundational gaps that need remediation before current-grade content makes sense. For example, a child struggling with multiplication might actually be missing fluency with addition facts, or a student struggling with reading comprehension might need phonics intervention.

Discuss possible learning differences if your child consistently struggles despite apparent intelligence and effort. Teachers can explain the school’s process for screening, evaluation, and intervention for students who may have learning disabilities, attention difficulties, or other factors affecting academic performance.

Create specific home support plans by asking “What exactly can I do at home?” Request specific practice activities, online resources, or routines that will reinforce classroom learning without creating homework battles or parental frustration.

Establish checkpoints for monitoring progress. Rather than waiting until the next formal conference to assess whether interventions are working, schedule brief check-ins via email or phone every 2-3 weeks to gauge improvement and adjust strategies as needed.

For schools implementing recognition programs that celebrate academic achievement, understanding specific goals helps your child work toward milestones worth celebrating.

Conference for High-Achieving Students

When students perform well above grade level, conferences should address enrichment, appropriate challenges, and continued growth rather than simply confirming that everything is fine.

Ask whether your child is appropriately challenged or whether they’re coasting on work that’s too easy. High achievement on grade-level work doesn’t necessarily mean a child is being stretched intellectually. Inquiry about differentiation strategies, advanced materials, or enrichment opportunities ensures continued growth.

Discuss work habits and effort even when grades are excellent. Students who achieve high marks with minimal effort may not be developing the persistence, problem-solving skills, and resilience they’ll need when coursework eventually becomes challenging. Ask whether your child demonstrates strong work ethic or whether success comes too easily.

Address social and emotional development alongside academics. Sometimes gifted students struggle socially with age-peers, experience perfectionism that creates anxiety, or feel isolated by differences in interests or maturity levels. High grades don’t automatically mean all is well emotionally.

Explore acceleration or enrichment options including advanced content within the current classroom, pull-out gifted programs, grade-level acceleration in specific subjects, participation in academic competitions or clubs, or independent study projects addressing individual interests.

Ask about executive function development including planning, organization, time management, and self-monitoring. These skills matter increasingly as academic demands grow, and high-achieving students sometimes struggle with them despite strong academic abilities.

Conference for Students with Behavioral Concerns

When behavior is the primary concern, conferences should move beyond simply cataloging problems to understanding causes and coordinating solutions.

Understand what the behavior looks like specifically by asking for detailed descriptions of when, where, and under what circumstances behavioral issues occur. Behavior that happens primarily during transitions might need different interventions than behavior occurring during academic instruction or unstructured social time.

Explore possible triggers or patterns including academic frustration manifesting as acting out, social difficulties creating anxiety that surfaces behaviorally, sensory sensitivities in the classroom environment, unclear expectations or inconsistent consequences, or attention-seeking when positive attention is scarce.

Discuss what’s working in addition to what isn’t. Even children with significant behavioral challenges have times, settings, or situations where behavior improves. Understanding what’s different during these better moments reveals potential intervention strategies.

Align home and school approaches so your child receives consistent messages, expectations, and consequences across both environments. When adults coordinate on behavior management strategies, children can’t play situations against each other and learn that expectations apply everywhere.

Consider whether evaluation is needed for underlying conditions like ADHD, anxiety, sensory processing differences, or other factors that affect behavior. Teachers can explain the school’s processes for behavioral support planning and evaluation referral when standard interventions prove insufficient.

Schools implementing character recognition programs often see improved behavior when positive choices receive public acknowledgment alongside academic achievements.

Conference for Students with Social Challenges

Social difficulties—from struggling to make friends to experiencing bullying to having conflicts with peers—deserve serious attention during conferences.

Understand your child’s social role in the classroom community by asking how they interact with peers, whether they have friends, how they handle conflict, whether they participate in group activities comfortably, and whether other children seek them out or avoid them.

Distinguish between different types of social challenges. A shy child who wants friends but struggles to initiate differs from a child who prefers solitary activities, which differs from a child actively excluded by peers, which differs from a child whose behavior pushes peers away. Each requires different support.

Ask what the teacher observes during unstructured times like recess, lunch, or transitions, when social dynamics become most visible. Many social challenges don’t surface during structured academic instruction but emerge clearly during free time.

Discuss whether bullying is occurring and if so, what the school is doing to address it. Schools have legal responsibilities to address bullying, so if this is a concern, be direct and ask specific questions about the school’s anti-bullying policies and interventions.

Explore social skills instruction or groups if available. Many schools offer social skills support through counselors or specialists, teaching explicit strategies for friendship, conflict resolution, emotional regulation, and peer interaction.

Consider outside interests that might build confidence and friendships around shared activities. Sometimes children struggle socially in the general school environment but thrive in specialized contexts like sports, arts, or clubs where they share interests with peers.

Making the Most of Virtual Conferences

Many schools now offer or require virtual parent teacher conferences via video platforms. These bring unique benefits and challenges.

Virtual Conference Advantages

Virtual conferences eliminate travel time and logistical challenges, making participation easier for working parents, those with transportation barriers, or families with young children at home. They create convenient options for parents unable to attend in-person evening conferences.

Digital formats often feel less formal and intimidating than face-to-face meetings, potentially encouraging more open communication. Screen-sharing allows teachers to show digital gradebooks, online portfolios, or specific assignments more easily than with paper copies.

Virtual Conference Preparation

Test your technology in advance. Verify that your device, internet connection, and conferencing software work properly before the scheduled time. Download any required apps, create necessary accounts, and ensure your camera and microphone function correctly. Technical difficulties eat into limited conference time and create frustration.

Choose an appropriate location with good lighting, minimal background noise, and privacy for confidential conversations. Avoid conferencing from cars, stores, or public spaces where interruptions or privacy concerns arise.

Minimize distractions by silencing phone notifications, closing unnecessary browser tabs, and informing household members you’re in an important meeting. Virtual meetings make multitasking tempting, but divided attention communicates disinterest and causes you to miss important information.

Position your camera at eye level showing your face clearly. Avoid extreme angles, backlighting, or distant positioning that makes it difficult for the teacher to see you clearly. Good video positioning maintains the personal connection that virtual formats can otherwise diminish.

Have materials ready including any documents you want to reference, your prepared questions, and note-taking materials, since you can’t spread papers out on a table as easily as in person.

Virtual Conference Etiquette

Join on time just as you would arrive on time for in-person meetings. If you encounter technical difficulties, use the teacher’s email or school phone number to communicate rather than simply being absent without explanation.

Minimize interruptions from pets, children, deliveries, or other household distractions as much as possible. While virtual meetings sometimes involve unexpected interruptions everyone understands, minimizing them shows respect for the teacher’s time.

Use video rather than attending audio-only when possible. Seeing each other’s facial expressions aids communication and maintains the personal connection that makes conferences valuable. However, if bandwidth issues make video problematic, audio-only is acceptable.

End respectfully by thanking the teacher for their time and confirming any next steps or follow-up needed before disconnecting. Avoid abrupt departures that feel dismissive.

After the Conference: Follow-Up and Implementation

The conference itself represents just one moment in an ongoing partnership. How you follow up determines whether conference benefits extend beyond the meeting itself.

Implementing Action Items

Review your notes soon after the conference while details remain fresh. Identify specific action items you committed to—whether reading with your child daily, practicing multiplication facts, enforcing consistent homework routines, or other home support strategies.

Share appropriate information with your child about what was discussed. The exact information you share depends on your child’s age, maturity, and the topics discussed. Elementary students might hear “Your teacher is really proud of how hard you’re working in reading” or “We talked about some strategies to help with math homework.” Older students might have more detailed conversations about academic goals, areas needing improvement, or next steps.

Communicate with other caregivers who weren’t present but share parenting responsibilities. Ensure everyone in your child’s life who needs to know about conference outcomes and action items has that information and understands their role in implementation.

Follow through consistently on strategies you agreed to try. Many interventions require sustained implementation over weeks or months to show results. Inconsistent follow-through undermines even well-designed plans and makes it impossible to assess whether strategies actually work.

Monitor progress using whatever indicators make sense for the specific goals you’re working toward. If addressing homework completion, track what’s turned in. If working on reading fluency, notice improvements in speed or accuracy. If targeting behavior, watch for changes in frequency or intensity of problematic behaviors.

Maintaining Communication

Use established communication channels the teacher prefers. Some teachers prefer email, others use school communication apps, some maintain weekly newsletters, and some send home weekly reports. Follow their system rather than inventing your own.

Respect communication boundaries around timing and frequency. Most teachers specify appropriate contact times and response timeframes. Sending multiple emails demanding immediate responses or contacting teachers during evenings and weekends except for emergencies shows disrespect for their time and personal lives.

Provide updates if your teacher asked you to monitor specific issues. If you agreed to track homework completion and report back in two weeks, follow through with that communication. If situations at home arise that might affect school performance—family illness, moving, divorce, death—let the teacher know so they can support your child appropriately.

Ask questions when confused rather than making assumptions. If an assignment seems unclear or you’re unsure how to help with something the teacher suggested, reaching out for clarification shows engagement rather than helplessness.

Share positives not just problems. When your child comes home excited about a lesson, proudly shows you improved work, or mentions something they enjoyed at school, send a brief note letting the teacher know. Positive feedback matters to teachers too, and communications that aren’t only complaints strengthen partnerships.

When Problems Persist

If issues discussed during the conference don’t improve despite consistent implementation of agreed-upon strategies, additional intervention may be needed.

Give interventions adequate time before concluding they aren’t working. Most strategies require several weeks of consistent implementation before you can fairly assess their effectiveness. However, if you’ve implemented plans consistently for the agreed-upon timeframe and aren’t seeing any improvement, further conversation is warranted.

Reach out proactively rather than waiting for the next scheduled conference. Contact the teacher saying something like: “We discussed [specific concern] at our conference and agreed to try [specific strategy]. We’ve been doing this consistently for [timeframe], but we’re not seeing the improvement we hoped for. Can we schedule a time to talk about next steps?”

Consider requesting additional resources including school counselors who can address social-emotional concerns, special education evaluation teams who can assess for learning disabilities, reading specialists who can provide intensive literacy intervention, or administrators who can help problem-solve persistent challenges.

Document carefully if you believe your child needs services they aren’t receiving or if you have serious concerns about how the school is handling a situation. Keep copies of emails, conference notes, and other communications. This documentation becomes important if disputes escalate to formal processes.

Understanding how positive school cultures support all students helps you assess whether your child’s school environment enables success and provides appropriate support when challenges arise.

Special Considerations for Different Grade Levels

Conference dynamics and priorities shift as children progress through school. These grade-specific considerations help you focus on developmentally appropriate concerns.

Elementary School Conferences (K-5)

Elementary conferences typically involve one teacher who teaches most or all subjects, making them efficient opportunities to understand your child’s overall progress. Key priorities include:

Foundation skills development in reading, writing, and mathematics receives heavy emphasis. Elementary teachers focus extensively on whether children are mastering fundamental literacy and numeracy skills that everything else builds upon. Ask specific questions about letter recognition, phonics, reading fluency, reading comprehension, number sense, basic operations, and problem-solving approaches.

Work habits and social development matter as much as academic content in elementary years. Teachers observe whether children can follow directions, work independently, stay on task, transition between activities, share and cooperate, manage materials, and regulate emotions—all crucial skills for future success regardless of academic content mastery.

Adjustment to school expectations particularly in kindergarten and first grade, where many children are still learning to navigate structured educational environments, follow routines, and function as parts of larger groups.

Parent involvement expectations are often highest in elementary school, when children need help with homework, reading practice, project materials, and basic organization. Clarify what level of home support the teacher expects and how to provide it effectively without creating dependence or conflict.

Many elementary schools implement student of the month recognition programs that celebrate academic effort, character, and growth mindset—all areas worth discussing during conferences.

Middle School Conferences (6-8)

Middle school introduces new challenges including multiple teachers, increased academic demands, complex peer relationships, and developmental changes of early adolescence. Conference priorities shift accordingly:

Multiple teacher conferences mean you may meet with 6-8 teachers in one evening, each for very brief periods. Some schools offer team conferences where all your child’s teachers meet with you together, while others schedule individual sessions. Either way, time is extremely limited, requiring focused questions about each subject.

Executive function development becomes increasingly important as students juggle multiple classes, teachers, assignment types, and long-term projects. Ask whether your child turns in work on time, uses organizational systems effectively, plans ahead for tests and projects, advocates for themselves when confused, and takes responsibility for their learning.

Peer influence and social navigation intensify during middle school years. Friendships, social hierarchies, peer pressure, and social media all significantly affect student experience. Ask how your child navigates these dynamics, whether they demonstrate resilience when social challenges arise, and whether concerning patterns suggest a need for intervention.

Preparation for high school begins during middle school. By 7th and 8th grade, conferences should address whether your child is on track for high school success, what academic challenges might need attention before high school, and how to select appropriate courses for freshman year.

Developmental changes affect behavior, emotions, and academic performance. Middle schoolers experiencing puberty, brain development changes, and increasing independence often show behavioral shifts that worry parents. Teachers can help you distinguish between normal adolescent development and concerning patterns requiring intervention.

High School Conferences (9-12)

High school conferences often focus more specifically on academic progress, post-graduation planning, and student independence. Dynamics differ significantly from earlier grades:

Student attendance becomes more common at high school conferences, with many schools expecting or requiring students to participate. This shifts conversations toward student self-advocacy and goal-setting rather than adults discussing students in their absence.

Academic rigor and college preparation dominate high school conferences, particularly for students planning post-secondary education. Ask whether your child’s course selections prepare them adequately for college or career goals, how they handle advanced coursework, and what additional challenges or support might be beneficial.

Specific subject-focused discussions occur when you meet with individual subject teachers. Unlike elementary conferences covering all subjects with one teacher, high school conferences address specific academic areas in depth. Come prepared with questions tailored to each subject rather than generic questions asked of every teacher.

Post-high school planning becomes increasingly important during 10th, 11th, and especially 12th grade conferences. Discuss college applications, career planning, vocational training options, military service, gap years, or other post-graduation paths. Ask how the school supports students in these transitions and what resources are available.

Independence and accountability should increase throughout high school years. By junior and senior year, students should be managing their academic responsibilities largely independently, with parents playing supportive rather than managerial roles. If your older high schooler still requires extensive parent management of schoolwork, conferences should address what skills need development for successful transition to college or career settings.

High school conferences often occur near school traditions like pep rallies and homecoming, creating natural opportunities to discuss not just academics but also your student’s overall high school experience and involvement in school community.

Building Year-Round Partnerships Beyond Conferences

While conferences provide valuable dedicated time with teachers, effective home-school partnerships extend throughout the entire year through consistent communication and engagement.

Establishing Communication Expectations

Early in the school year, clarify communication preferences, protocols, and boundaries with your child’s teacher. Understand their preferred method of contact (email, phone, school app), typical response timeframes, and appropriate times for non-emergency communication.

Ask about regular communication rhythms—weekly newsletters, monthly progress reports, or other routine updates—so you know what information to expect without asking. Clarify what types of situations warrant parent notification: only serious concerns, or also positive developments and minor issues worth knowing about.

Discuss whether your child’s teacher uses digital platforms for posting assignments, grades, or other information, and ensure you have necessary login credentials and understand how to access and interpret information.

Participating in School Community

Active involvement in school community strengthens partnerships with teachers and enhances your child’s experience. Consider participating in:

Parent-teacher organizations (PTO/PTA) that coordinate family engagement activities, volunteer opportunities, and school support initiatives. Even occasional participation demonstrates investment in your child’s school community.

Volunteer opportunities in classrooms, libraries, field trips, or special events provide firsthand observation of your child’s school environment while building relationships with staff. Teachers appreciate parent volunteers who free them to focus on instruction rather than logistical tasks.

School events like performances, athletic competitions, open houses, and recognition ceremonies show your child that their school activities matter to you while helping you understand the school culture and community.

Information sessions about curriculum, assessment, or special programs help you understand what your child is learning and how the school approaches education.

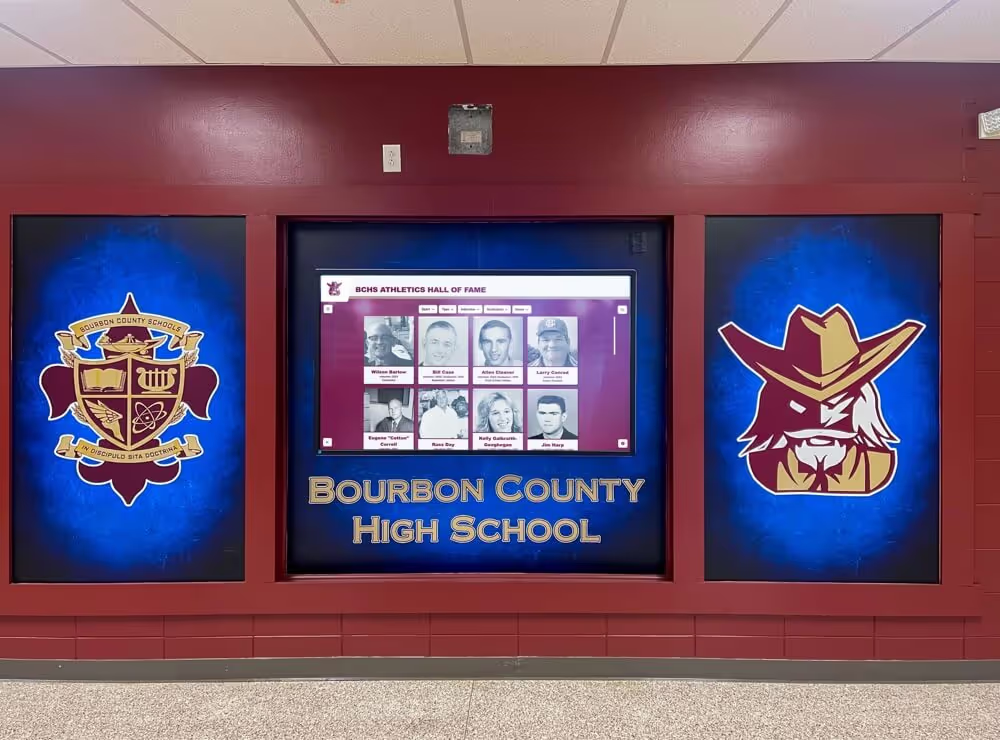

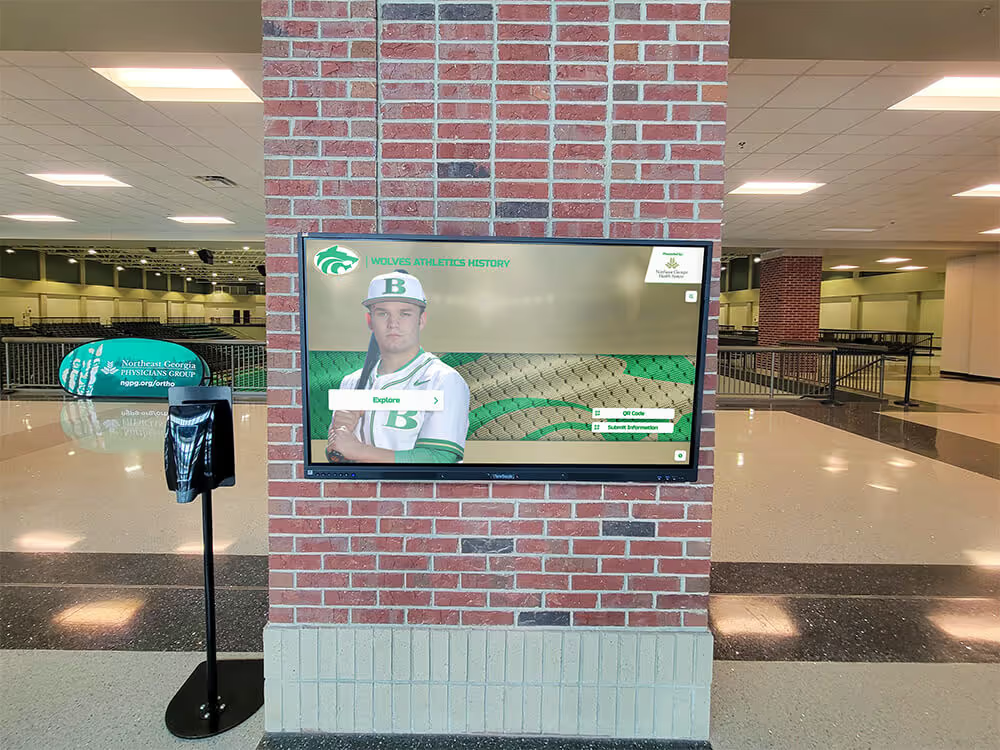

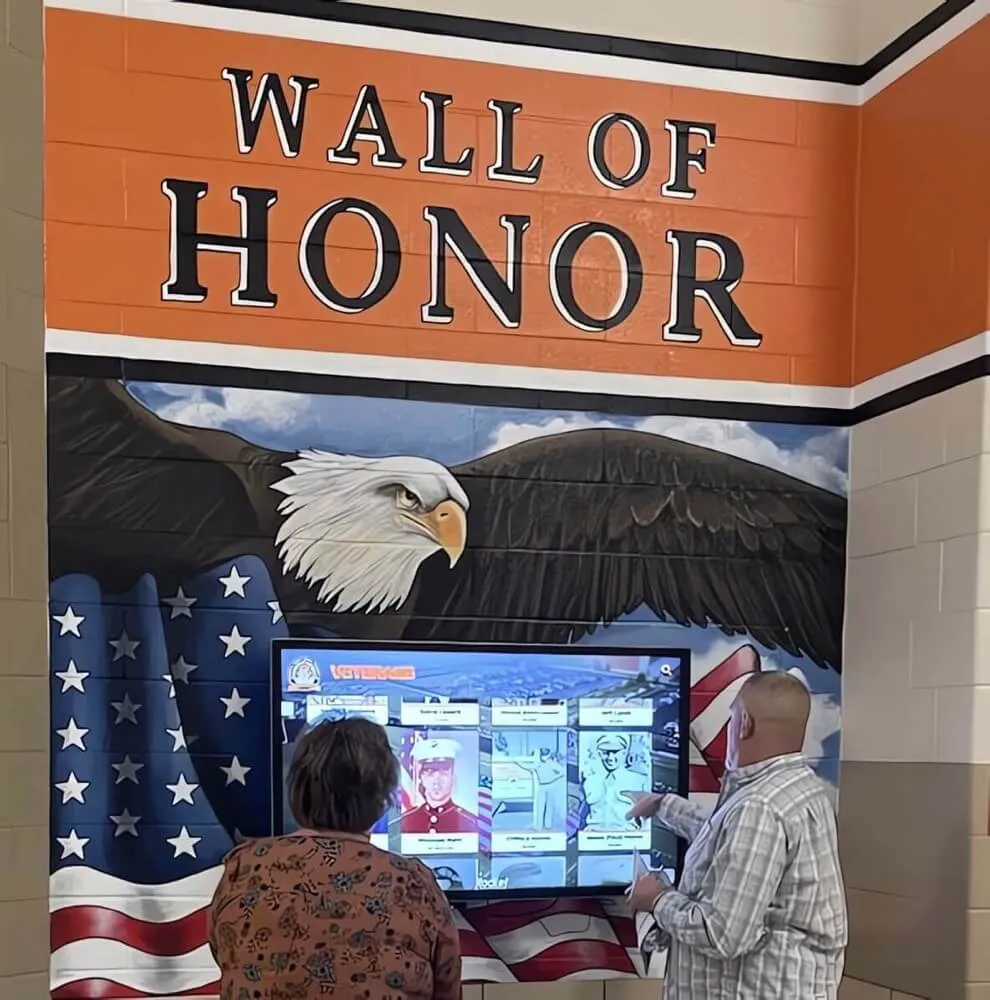

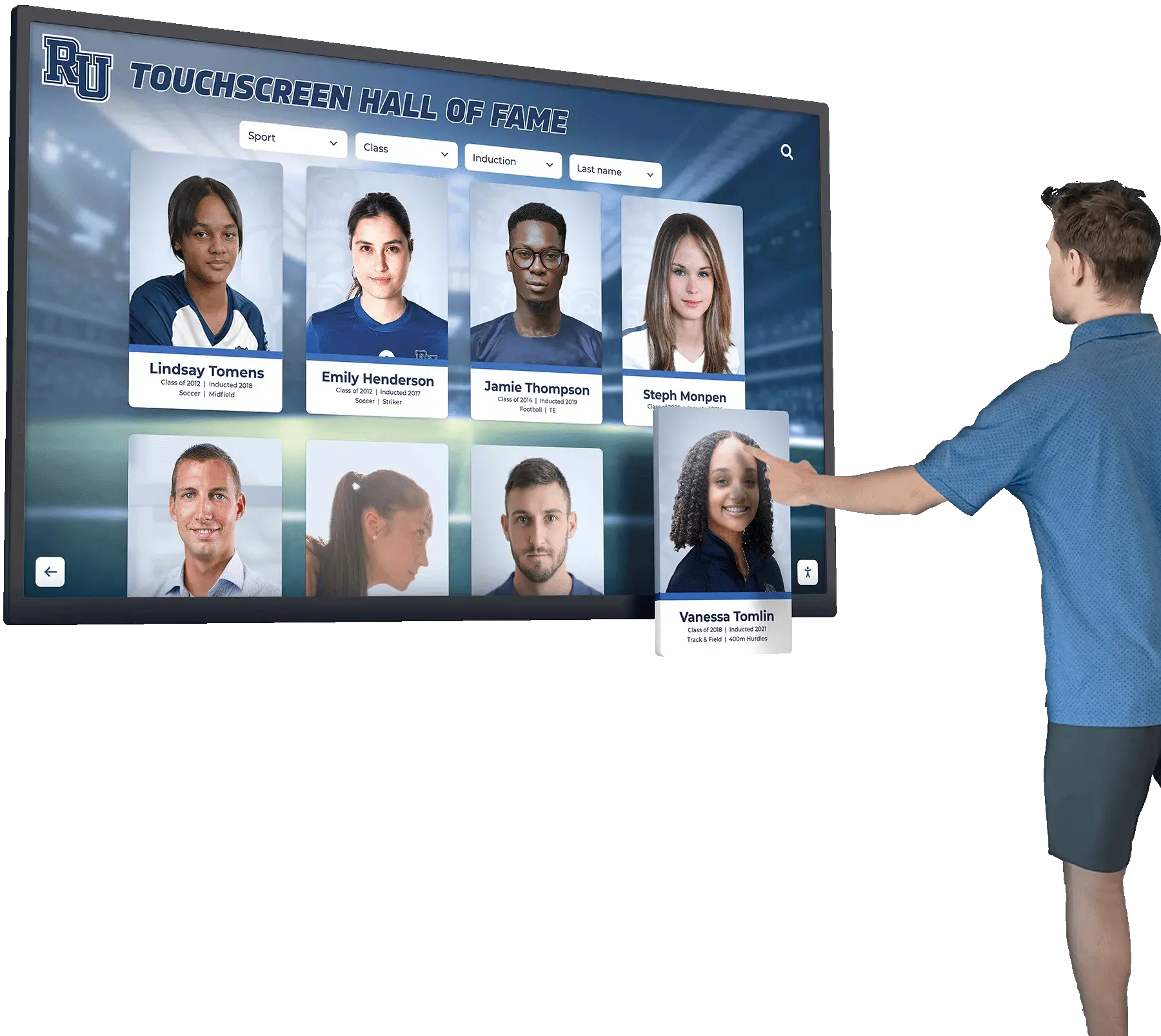

Many schools use modern digital recognition displays in lobbies and common areas to celebrate student achievement, honor school history, and build community pride. These displays provide conversation starters when visiting school and help you understand what accomplishments the school values and celebrates.

Supporting Learning at Home

Effective home support for learning doesn’t require parents to become substitute teachers or homework police. Instead, focus on creating environments and routines that enable student success:

Establish consistent routines for homework, reading, and organization that reduce daily negotiations about when and where schoolwork happens. Consistency matters more than perfection.

Provide appropriate space and resources including adequate lighting, minimal distractions, necessary supplies, and access to technology when required for assignments.

Show interest without micromanaging by asking about what your child is learning, looking at completed work, and discussing school experiences without hovering over every assignment or correcting every error yourself.

Model lifelong learning through your own reading, curiosity, problem-solving, and intellectual engagement. Children who see adults valuing learning are more likely to value it themselves.

Maintain perspective about grades and achievement. While academic performance matters, so do character development, social-emotional wellbeing, physical health, and childhood experiences beyond academic metrics. Balance appropriately high expectations with recognition that childhood isn’t solely preparation for college admissions or career success.

Common Conference Mistakes to Avoid

Even well-intentioned parents sometimes undermine conference effectiveness through common missteps. Avoiding these mistakes improves conference productivity.

Arriving Unprepared

Arriving at conferences without having reviewed recent work, checked grades, or prepared questions wastes precious time on information gathering that should happen before the meeting. This leaves insufficient time for substantive discussion about your child’s needs and appropriate support strategies.

Dominating the Conversation

Conferences work best as dialogues where both parents and teachers share information and perspectives. Parents who monopolize conversation time with excessive detail about home circumstances, lengthy stories about their own school experiences, or extended monologues about their child prevent teachers from sharing their observations and expertise.

Becoming Defensive

When teachers raise concerns, defensive reactions—denying problems exist, blaming teachers for difficulties, making excuses for every issue, or attacking teaching methods—shut down productive problem-solving. Even when you disagree with a teacher’s assessment, maintaining composure and seeking to understand their perspective before responding allows for more productive outcomes.

Making Comparisons

Comparing your child to siblings (“His brother never had trouble with math”), classmates (“Why does he struggle when other kids don’t?”), or your own childhood (“I never needed help with homework when I was his age”) rarely helps. These comparisons ignore that every child is unique with different strengths, challenges, learning styles, and circumstances.

Ignoring the Teacher’s Perspective

Dismissing teacher concerns with “He’s fine at home” or “She’s just bored because the work is too easy” without exploring why discrepancies exist between home and school environments misses opportunities to understand your child more completely and address issues before they become serious.

Dwelling Only on Problems

Conferences that focus exclusively on concerns without acknowledging strengths, progress, or positive qualities create unnecessarily negative experiences. Even when serious issues need discussion, balanced conversations that recognize the whole child maintain more productive partnerships.

Failing to Follow Through

Agreeing to strategies, interventions, or follow-up during conferences but then not implementing them at home undermines both the conference process and your child’s progress. Teachers notice when promised follow-through doesn’t occur and may become less invested in partnership as a result.

Advocating Effectively for Your Child

Effective advocacy means ensuring your child receives appropriate education and support without becoming adversarial or unreasonable.

Understanding the Difference Between Advocacy and Adversarialism

Good advocacy operates from the premise that parents and schools share common goals and works collaboratively toward solutions. It involves clearly communicating your child’s needs, requesting appropriate services or accommodations, following up persistently but respectfully when concerns aren’t addressed, asking for clarification when confused about decisions or policies, and seeking solutions at the appropriate level before escalating.

Adversarial approaches that damage partnerships include assuming bad faith or incompetence from school staff, making threats about legal action or complaints as first resorts, refusing to consider any perspective other than your own, demanding special treatment that’s unreasonable or impractical, and going immediately to administrators or school boards without attempting to resolve issues with teachers first.

When Escalation Is Appropriate

Most concerns should be addressed with classroom teachers before involving others. However, escalation becomes appropriate when teachers are non-responsive to repeated attempts at communication, they dismiss significant concerns without investigation or explanation, issues involve serious safety or wellbeing concerns, legal rights or protections are at stake, conflicts with teachers can’t be resolved directly, or you need services requiring administrative approval.

Even when escalating, maintaining respectful communication and clear documentation of your attempts to resolve issues at lower levels demonstrates you’re acting reasonably rather than simply bypassing the chain of command.

Resources for Complex Situations

When conferences reveal needs beyond typical classroom support, various resources may help:

School counselors address social-emotional concerns, behavioral challenges, peer relationship difficulties, and mental health needs.

Special education teams evaluate and serve students with disabilities affecting learning or behavior, providing individualized education plans (IEPs) with specialized instruction and accommodations.

504 coordinators implement plans providing accommodations for students with disabilities that don’t require special education services but do need modifications to access general education.

Reading specialists provide intensive literacy intervention for students significantly behind in reading skills.

School psychologists conduct academic and behavioral assessments, provide counseling, and assist with learning and behavior support.

Community resources including mental health services, tutoring programs, and enrichment opportunities supplement school support when needs exceed what schools can provide alone.

Understanding how schools preserve and celebrate diverse student achievements helps you recognize the full range of ways students can succeed and be recognized beyond traditional academic metrics alone.

Maximizing Conference Value for Different Family Situations

Family circumstances vary widely, and conference approaches may need adaptation based on your specific situation.

Single Parent Conferences

Single parents managing conferences alone often face time pressures, childcare challenges, and lack of another adult to debrief with afterward. Request first-available or last-available time slots to minimize complications with work schedules or childcare. If possible, bring another trusted adult—a grandparent, family friend, or other support person—to conferences when discussing complex concerns. Two sets of ears hear more completely than one, and another adult can help you process information afterward.

Co-Parenting After Divorce

When parents co-parent from separate households, clarify with the school which parent(s) should attend conferences and how information will be shared. Some schools schedule separate conferences for each parent, while others expect both to attend together. Be clear about communication preferences, legal custody arrangements, and information-sharing permissions.

Put your child’s needs ahead of adult conflict by maintaining professionalism during conferences even if relationships with your co-parent are strained. Teachers shouldn’t become messengers between divorced parents or referees for adult disputes.

Language Barriers

If English isn’t your primary language, request an interpreter for conferences well in advance. Schools are legally required to provide interpretation services ensuring you can participate fully. Don’t rely on your child or older siblings to interpret during conferences—adult interpreters maintain confidentiality and translate accurately without being caught between parent and teacher perspectives.

Prepare questions in advance and if possible, have them translated so you can follow along even if interpretation lags slightly behind the conversation.

Parents of Children with Disabilities

If your child has an IEP or 504 plan, conferences should address not only general progress but also whether accommodations and services are being implemented as written and whether they’re effective. Bring copies of the IEP or 504 plan to reference during conversation.

Consider requesting extended conference time if your child’s needs require more discussion than standard slots allow. Schools should accommodate reasonable requests for additional time when discussing students with significant special needs.

Understand that parent-teacher conferences differ from IEP meetings, which are separate formal processes involving broader teams. Don’t try to resolve all IEP concerns during regular conferences—request formal IEP team meetings when needed.

Working Parents with Limited Availability

When work schedules conflict with standard conference times, don’t simply skip conferences. Request alternative arrangements including before-school or lunch-time slots, virtual conferences that eliminate commute time, brief phone conferences if face-to-face meetings aren’t possible, or written communication followed by a phone call to discuss questions.

Most teachers willingly accommodate reasonable scheduling requests rather than have parents unable to participate at all.

Conclusion: Conferences as Foundations for Partnership

Parent teacher conferences represent far more than routine check-ins on report card grades. These brief meetings create foundations for ongoing partnerships between home and school—partnerships that dramatically influence student success, wellbeing, and development across the school years.

When parents arrive prepared with relevant questions and open minds, when teachers share honest assessments balanced with respect and care, and when both parties commit to collaborative problem-solving focused on the child’s best interests, conferences transform from obligatory events into powerful tools for supporting student growth.

The most effective conferences share common elements: preparation from both parties who gather information and organize thoughts beforehand, honest communication that addresses both strengths and concerns directly but respectfully, collaborative problem-solving that generates specific action plans rather than vague intentions, mutual respect recognizing that both parents and teachers bring valuable expertise about the child, and follow-through implementing agreed-upon strategies with consistency and checking progress regularly.

Remember that conferences are moments in time within longer relationships. How you follow up matters as much as the conference itself. Implementing strategies you agreed to, maintaining appropriate communication throughout the year, supporting your child’s learning at home, and participating in school community all extend the partnership beyond 15-minute meetings.

Whether your child is thriving, struggling, or somewhere in between, conferences provide opportunities to celebrate growth, address challenges early before they become serious, align home and school expectations and support, build relationships with teachers that benefit everyone involved, and demonstrate to your child that their education matters to the adults in their life.

As schools increasingly embrace modern recognition technologies celebrating diverse student achievements and creating more visible pathways to success, conferences become opportunities not just to address concerns but also to identify your child’s strengths and find ways for them to contribute to and be recognized within their school community.

Approach your next parent teacher conference not as an intimidating obligation but as a valuable opportunity—a chance to gain insights about your child from someone who sees them in a completely different context, to share information only you know as their parent, and to build a partnership that will support your child’s journey toward becoming their best self.

Ready to learn more about how schools are transforming recognition and family engagement? Explore innovative solutions that help schools celebrate student achievement, preserve institutional history, and strengthen community connections through modern digital platforms designed specifically for educational environments.